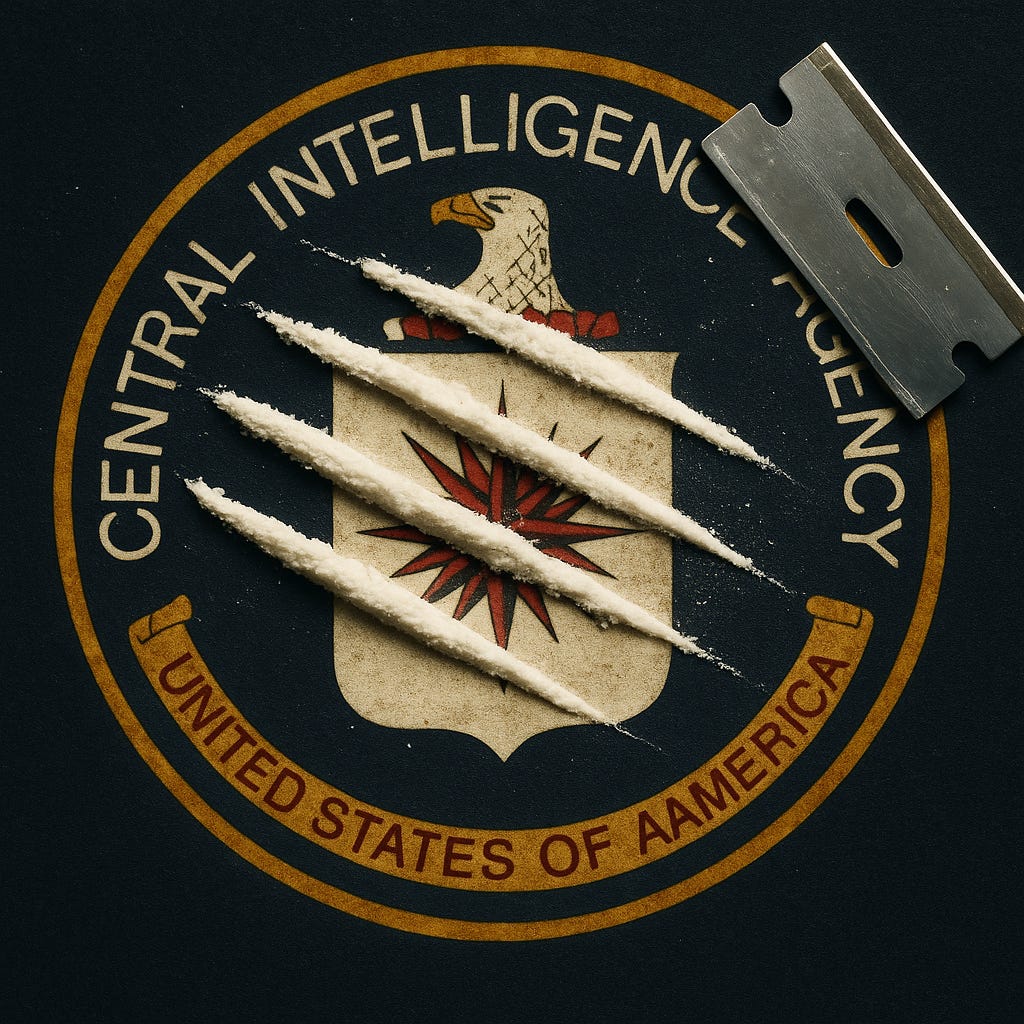

Weekend Read: The CIA's Cartel

Trump officials are said to be preparing to justify strikes on Venezuela by invoking the “Cartel of the Suns." History shows that the same network once operated inside a CIA-run anti-drug program.

The Trump administration wants to bomb Venezuela’s “Cartel of the Suns.” Three decades ago, members of that same cartel were fighting the drug war with the CIA.

According to The New York Times, Justice Department lawyers are drafting a legal rationale for an attack on Venezuela based on President Nicolás Maduro’s role as leader of a drug-trafficking organization—the Cartel de los Soles, or “Cartel of the Suns.” The designation would allow the White House to conduct military strikes without congressional authorization, skirting the longstanding U.S. ban on political assassinations.

Prosecutors in New York indicted Maduro on narco-terrorism conspiracy charges in 2020, alleging that under his leadership, the Cartel de los Soles sought not only to enrich its members but to “flood” the United States with as much Colombian cocaine as possible.

We’ve been here before. In 1989, U.S. forces invaded Panama to remove Manuel Noriega, a former CIA collaborator who had become a drug-running dictator and, in the words of a Senate investigation, built “the hemisphere’s first narcokleptocracy.”

But the origins of Venezuela’s Cartel of the Suns tell a different story, one the U.S. government would rather not revisit. (A CIA spokeswoman said the agency would provide a response for this story, but ultimately did not comment.)

I learned about the CIA’s Venezuelan drug operation while reading intelligence historian

’s post on the subject. The allegations were startling enough on their own: that the agency had looked the other way while a ton of cocaine moved onto American streets. But the reason for this detour into the past is simple. The same institutional framework the CIA helped build, the same military networks it empowered, now form the basis for a cartel the United States may be preparing to go to war against.Cartel de los Soles

The name Cartel de los Soles originated in 1993 when Brigadier General Ramon Guillen Davila and his successor were first accused of trafficking, according to InSight Crime, a think tank that studies organized crime. The “suns” referred to the insignia the Venezuelan generals wore on their epaulettes.

Guillen, the anti-drug chief of the Guardia Nacional (National Guard), was once one of the CIA’s most trusted partners in the region. The agency built and financed a special intelligence unit within the National Guard, headed by Guillen. But Venezuela’s top drug warrior was also an alleged cocaine smuggler

The CIA operation, approved under President Ronald Reagan, was designed to gather intelligence on Colombian cartels by inserting agents into the smuggling pipeline. In 1986, Reagan had declared global drug trafficking a threat to U.S. national security and directed the CIA to target international traffickers with suspected links to terrorist or insurgent groups. (Trump has blurred the distinction between terrorists and drug smugglers to justify lethal strikes that have killed 80 people aboard suspected drug-smuggling vessels.)

A civilian informant working with Guillen, Adolfo Romero Gomez, served as a key middleman between Colombian suppliers and traffickers in South Florida. Through Guillen, Romero kept both the CIA and the DEA informed about so-called “controlled deliveries” of cocaine into Miami—shipments allowed to move under surveillance in hopes of snaring major players and seizing the drugs.

The Operation Unravels

The operation ran for a few years until late 1990, when the CIA began to suspect that Guillen and Romero were skimming cocaine from those controlled shipments. A DEA investigation found that a ton of nearly pure cocaine that had been shipped under the auspices of the CIA anti-drug program wound up on the streets of the United States.

The CIA said it had been hoodwinked. The DEA wasn’t so sure.

In 1992, Guillen was arrested in Venezuela on local drug trafficking charges, but the charges were later dropped by a judge.

Four years later, a Miami grand jury indicted Guillen for conspiring to smuggle 22 tons of cocaine into the United States between 1987 and 1991. Venezuela declined to extradite him.

Romero was less fortunate. Arrested in Colombia, he was extradited to Miami, convicted of cocaine-conspiracy charges, and sentenced to nearly 20 years in prison.

Romero’s 1997 trial featured a rare sight: a former CIA officer testifying about the agency’s “liaison” relationship with a foreign service, a category of information the agency guards almost as tightly as the names of its spies. The initiative meant to cripple a Colombian cartel instead collapsed in scandal and ended his career.

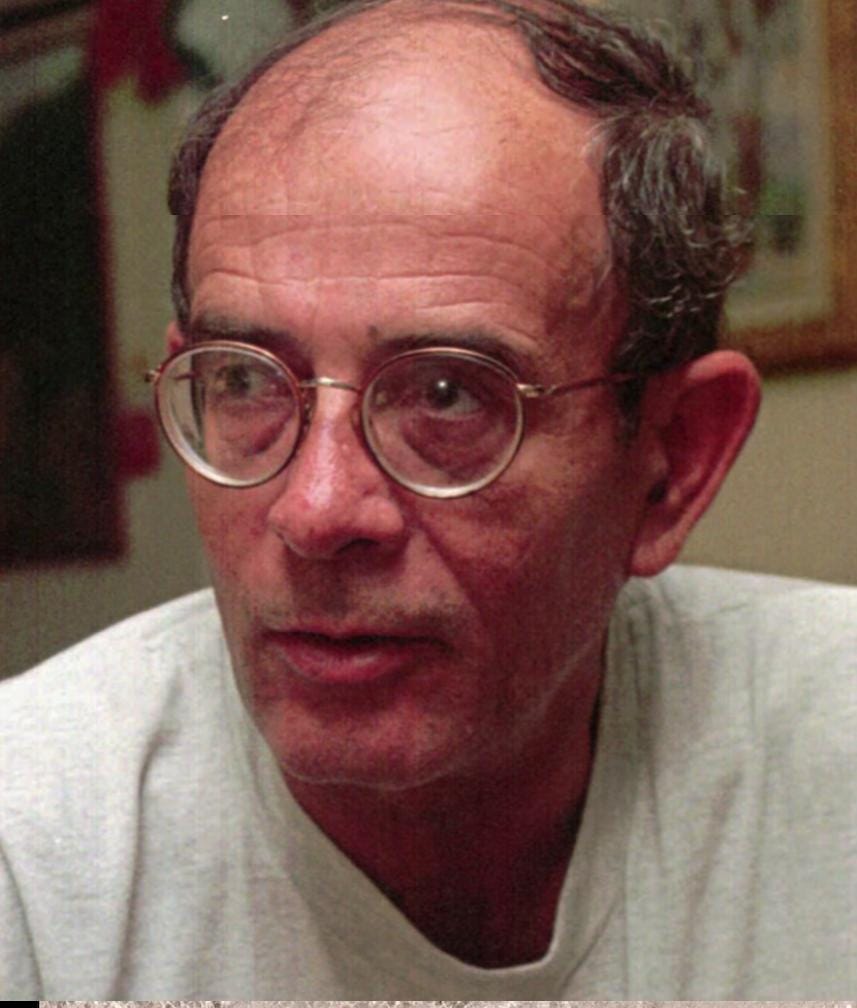

Mark McFarlin, the former officer who had worked closely with Guillen, told the court the agency had trained and equipped the National Guard’s intelligence center in Caracas, teaching officers spy tradecraft and agent handling. “We offered a comprehensive package,” McFarlin testified, according to The Miami Herald. Guillen told the Caracas newspaper El Nacional that the CIA spent $1.3 million on the center.

In Venezuela, the CIA struck an anti-drug partnership with the National Guard that operated separately from the DEA and Venezuela’s own police and intelligence services. The Caracas CIA station deliberately kept the DEA in the dark about key operations.

The extent of that secrecy became clear at Romero’s trial. According to The Miami Herald’s account of later court testimony, when trucks hauled 3,000 pounds of Colombian cocaine into Venezuela for storage and later export, McFarlin notified his boss, station chief James Campbell.

“Did the DEA know about the shipment?” Campbell asked.

“No,” McFarlin said.

“Let’s keep it that way.”

McFarlin was asked to resign after an internal review cited “instances of poor judgment and management” but found “no evidence of criminal wrongdoing.” Campbell was recalled, promoted, and quietly retired.

Langley’s Smugglers?

In Washington, officials framed the affair as the work of a corrupt general who had deceived his CIA handlers. But a 60 Minutes investigation in 1993 that broke the story suggested McFarlin and Campbell were hardly innocent.

Annabelle Grimm, the DEA’s agent-in-charge in Caracas, told correspondent Mike Wallace that McFarlin and Campbell met with her seeking her agency’s approval to let hundreds of pounds of cocaine flow onto American streets. “They wanted to let it come up to the United States—no surveillance, no nothing,” she said.

The CIA told Grimm that allowing these “uncontrolled” shipments into the United States would earn the trust of cartel bosses. “They thought they were going to get Pablo Escobar at the scene of the crime or something, which I found personally ludicrous,” she said.

The DEA rejected the plan, but it happened anyway. “I really take great exception to the fact that 1,000 kilos came in, funded by U.S. taxpayer money,” Grimm said. “I found that particularly appalling.”

The CIA told Congress it had warned the Venezuelans not to proceed, but Grimm doubted the agency had been deceived. “General Guillen and his officers didn’t go to the bathroom without telling Mark McFarlin or the CIA what they were going to do,” she said.

Robert Bonner, a former head of the DEA, said the CIA was complicit in drug smuggling. “I don’t think there’s any other way you can rationalize around it, assuming, as I think we can, that there was some knowledge on the part of CIA,” Bonner told Mike Wallace. No one from the agency was ever prosecuted.

It fit a familiar pattern. In 1989, a Senate subcommittee led by Senator John Kerry was the first to document that U.S. officials had knowingly tolerated drug trafficking by General Noriega and others under the guise of national security. “In the name of supporting the Contras,” the Kerry Committee found, “we abandoned the responsibility our government has for protecting our citizens from all threats to their security and well-being.”

Guillen remained in Venezuela, where he was arrested again in 2007 and accused of conspiring to kill Hugo Chávez. He has since died.

The Cartel de los Soles evolved over the decades, as Venezuelan military and intelligence officials have allegedly continued the pattern of profiting from drug trafficking and turning the country into a global hub for cocaine trafficking and money laundering. But as InSight Crime notes, rather than a hierarchical organization with Maduro directing operations, it’s more accurately described as a “system of corruption” where military and political officials profit by working with traffickers

Today, the same narrative that once shielded a CIA-backed drug operation is being revived to justify military action. The Cartel de los Soles—a phrase born from the corruption of Venezuelan generals working with U.S. intelligence—is emerging as the centerpiece of the Trump administration’s case for strikes against Venezuela.

Seth here—Thanks to all who commented on my last piece. The responses were great and will help me deliver a better product for you. Based on your suggestions, I will incorporate more source documents into the story going forward, as I did today. And thanks for sticking with me on this deep dive into CIA history, which is one of my interests. As always, please let me know your thoughts in the comments.

gary webb dark alliance. nicaraguans. Eugene Hasenfus. barry seal. clinton. bush. reagan. iran contra. oss in china/burma/india. opium. air america. product that doesn’t move through banking systems. no congressional budget required. no congressional oversight. afghan opium. dea never did get poppy production in hand. strange. business as usual.